Big Work in Elementary Classrooms

Laura Mazer

Senior Vice President of Programs

I was visiting a Guidepost elementary classroom recently, and met a student hard at work creating a book of limericks. He had recently had a lesson on poetic forms, and fell in love with the humor, the spark, the verve of the limerick. He decided to make his own book. It took a lot of work: he made the book itself, binding the pages together with thread. He convinced several classmates to author their own limericks to contribute, on topics ranging from favorite pets to complaints about siblings. And he illustrated each one with a drawing in pastels.

The result was beautiful. It was a combination of poetry, art, and hand work that combined multiple lessons into something new and unique. It was big.

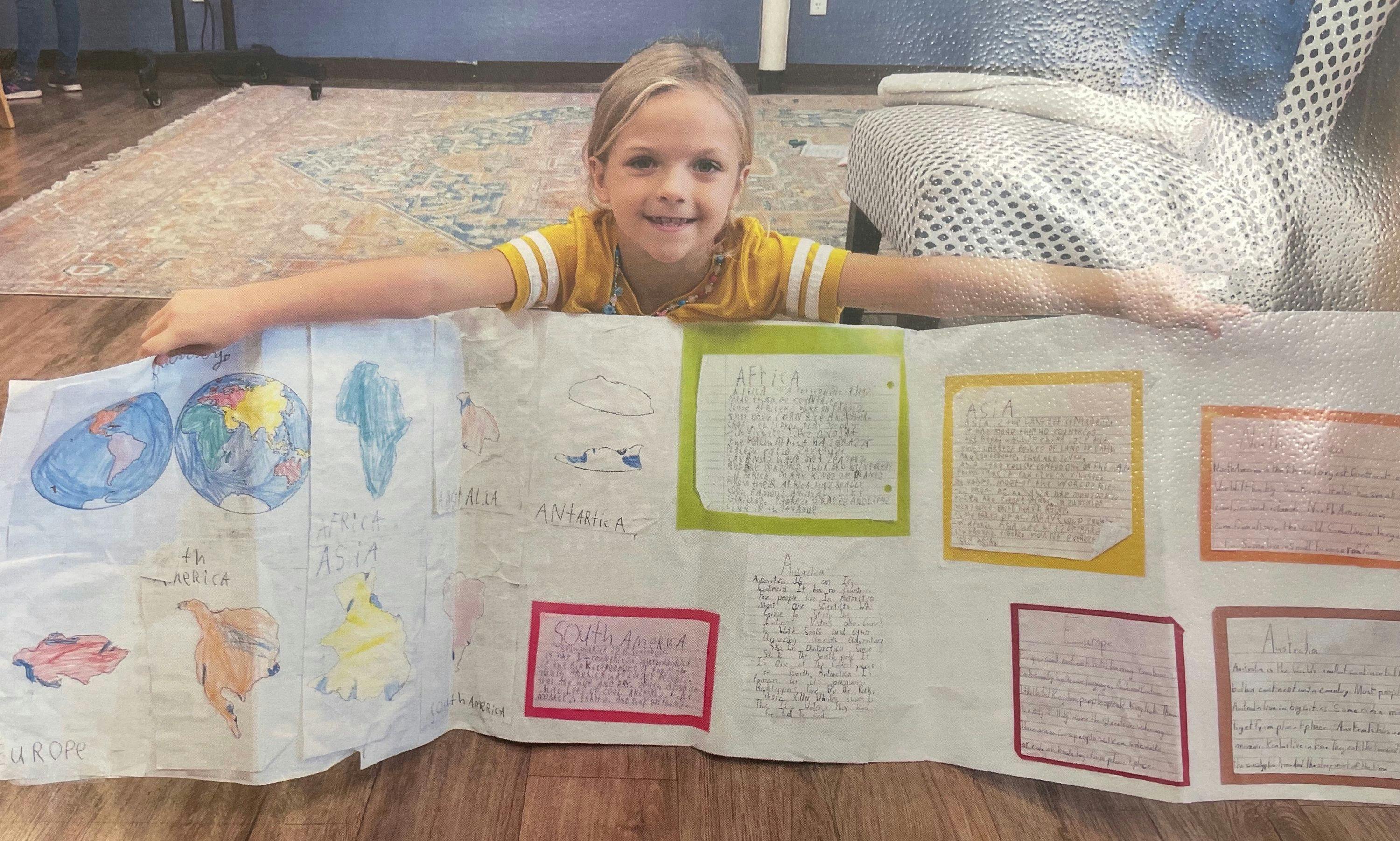

Big Work is a core component of a Montessori elementary classroom. It doesn’t need to be physically big—the book of limericks was only about six inches high. But it often IS physically big—huge timelines of history that span the entire room, full-size animals made of paper mache, or a salt-dough human skeleton. But, big or small, it represents an elementary child’s unique expression of mastery over the academic content.

In the Children’s House classroom (2.5 to 6-year-olds), children repeat activities over and over again. At this age, a child’s main need is for physical independence: mastery of their own body, hands, and surroundings. The path towards fine motor skills is practice—and as a result, children have an innate drive to reach for the same material over and over until they have truly mastered the actions.

The elementary age child, however, no longer finds satisfaction in repetition. She is ready to move beyond repetition and into elaboration. After getting a lesson on the large bead frame and feeling confident in adding numbers to the millions, she will quickly look for an opportunity to go bigger and do more.

The result might look like a huge sheet of graph paper where she adds up the biggest numbers she can imagine, in seemingly endless lines. For another student, an anatomy lesson on the digestive system can lead to a three-dimensional sculpted intestine—life sized! At this stage of development, children are primarily searching for intellectual independence. Similar to the younger child who is driven to tie his shoes, deliberately, thoughtfully, repetitively, the elementary child is driven to take the content in the classroom and make it bigger.

What are the elements of Big Work?

- Lessons: Big Work requires students to pull from, and elaborate on, a toolbox of skills and knowledge.

- Materials: Huge poster boards, timeline paper that can stretch from wall to wall, markers, paints,clay, and pastels that invite students to explore.

- Uninterrupted work periods: This kind of work doesn’t get done in a 40-minute math class, or as homework. The full, three-hour open-ended work cycle of a Montessori classroom provides the time to focus deeply and create something unique, no matter how long it takes.

- Expectations for excellence: Big Work requires a lot of meticulous effort. The student who created a book of limericks had written a first draft of each limerick, by hand, and asked his teacher for edits. Only then did he copy the poems, in beautiful cursive, into the book. A culture of revisions, of multiple drafts, and of high standards is essential for Big Work to happen.

- The children themselves: One of the reasons Big Work is so magical is that no two students will create the same thing. The same lesson on anatomy, in the same classroom, with the same materials and expectations, will lead to a salt-dough skeleton from one child, an illustrated book from a second, and a timeline of historical discoveries from a third. It is the magic of the elementary age to take what is offered—lessons, materials, work time, and expectations—and combine them in ways that are new and wonderful.

Elementary age children crave the opportunity to create. Think of the younger child who becomes frustrated and cries if he is denied the opportunity to push an elevator button or to zip up his own jacket. He is being denied his very real need to gain independence over his physical surroundings. The elementary child may not throw a tantrum—she may not cry or pout immediately. Instead, she will often simply turn away from work: denied the opportunity for intellectual independence, for taking the lessons in new and creative directions, she will conclude that school is uninteresting. Learning is not for her. And tragically, a spark will go out.

The magic of Montessori for elementary children is the recognition of this fundamental need, and an environment designed to support it. Come visit our elementary classrooms and see the Big Work that happens there!